마인:마켓인사이트

[영어기사/Bloomberg] Amazon Unveils Biggest Grocery Overhaul Since Buying Whole Foods_20230802 본문

[영어기사/Bloomberg] Amazon Unveils Biggest Grocery Overhaul Since Buying Whole Foods_20230802

Insight-er 2023. 8. 2. 19:16It’s revamping stores, unifying online shopping carts and offering fresh-food delivery to customers who aren’t Prime subscribers.

Amazon.com Inc. is launching the biggest overhaul of its grocery business since it acquired Whole Foods Market six years ago—revamping stores, testing new highly automated warehouses and, for the first time, offering fresh-food delivery to customers who aren’t Prime subscribers.

In a move likely to play well with shoppers, the company also plans to merge its various e-commerce supermarket offerings—from Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh, Amazon.com—into one online cart.

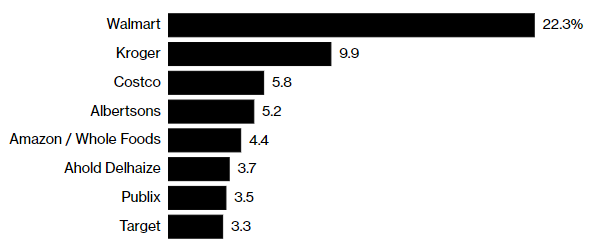

The changes, which will roll out in the coming weeks and months, mark the Seattle-based company’s latest effort to grab a bigger share of a US grocery market that UBS Group AG analysts estimate is worth $1.5 trillion. The tech behemoth has elevated a slate of more traditional retail executives to help. Tony Hoggett, the former Tesco Plc executive leading the charge, has deep brick-and-mortar experience but confronts a landscape dominated by the likes of Walmart Inc. and Kroger Co.

US Grocery Market Share by Retailer

In an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, Hoggett, 49, describes the company’s ambitions to transform Amazon from something of a niche grocer specializing in organics and home delivery of cereal and paper towels into a destination for shoppers trying to stretch their dollars and consolidate trips to the store. “We’re serious about grocery,” he says. “Our plan is on building this really strong grocery relationship with customers over time.”

On Aug. 2, Amazon will begin inviting people without Prime subscriptions in a dozen US metropolitan areas—including Boston, Dallas and San Francisco—to order groceries online from Amazon Fresh stores and warehouses. Previously, only shoppers paying the annual $139 Prime subscription could get food delivered from Fresh. The company aims to make the offer standard nationwide by the end of the year and eventually include products from Whole Foods and other grocers. Delivery fees range from $7.95 to $13.95, or $4 more than Prime members pay.

Amazon customers have long expressed frustration that they need to check out from three separate web pages to get everything on their shopping lists. Consumers who want king salmon fillets (sold by Whole Foods), a pack of shredded lettuce (sold by Amazon Fresh) and a box of Cheerios (sold, with other shelf-stable products, by Amazon.com) sometimes found themselves making three different orders—ferried to their homes in three separate deliveries. The company is looking to simplify the process this year or next by stocking more Whole Foods products in Amazon warehouses and creating one cart. “We recognize that still needs to be improved,” says Hoggett, the senior vice president for worldwide grocery stores.

In the physical world the company is revamping its Fresh stores, placing Krispy Kreme coffee and doughnut stands near the front door, adding roughly 1,500 items to what had been limited inventory for a full-size supermarket and trying to make the space more inviting with bright colors. Grocery analysts and some shoppers were turned off by the chain’s sterile, utilitarian design. “It just feels soulless,” says Peter Abraham, a marketer in Los Angeles who dropped in on a Fresh store a few times and has stopped going back.

Amazon’s rationale for being in the famously low-margin grocery business is much the same as Walmart’s: to use regular pantry refills to drive traffic and coax shoppers to buy other products. Over the past few years, Amazon has built a large online business selling such staples as paper products, canned goods, pet food and health and beauty items. Those sales were supercharged when the pandemic forced many people to shop online for groceries and consumables for the first time.

But the company has been trying for years to figure out how to profitably sell fresh food, starting and killing a range of initiatives. Delivering meat and produce is logistically challenging and expensive. Two people familiar with the situation, who requested anonymity to discuss an internal matter, say Amazon required a grocery order of about $115 to break even in 2010, on average. A decade later that break-even point was still $90 to $100. Hoggett says the company doesn’t track delivery economics using a single figure because of differences in order speed and types of trips, but he says the company had made “big steps” in building a more efficient home delivery business.

One solution is physical stores, which can double as pickup locations and mini-fulfillment centers. The $13.7 billion Whole Foods purchase wasn’t enough, because the chain operates only about 530 stores, compared with Walmart’s thousands. So in 2020 the company launched the Amazon Fresh grocery chain, which offers curbside pickup and serves as a staging point for home delivery. The first Fresh store opened in Los Angeles in September of that year, and the company seemed poised to add hundreds more in short order as an aggressive real estate team scooped up space in strip malls and shopping centers across the US.

Then, Andy Jassy succeeded Jeff Bezos as chief executive officer and slammed the brakes on spending as his team reviewed the company’s biggest bets, including the grocery business. Amazon shuttered more than 60 brick-and-mortar locations last year, including bookstores, a potpourri mart called Amazon 4-star and pop-up electronics stores in shopping malls. Hoggett paused the grocery expansion last fall, and the company at the end of the year took a $720 million writedown primarily related to its grocery business, reflecting store closures and broken leases, among other things.

Jassy and Hoggett’s boss, worldwide retail chief Doug Herrington, approved the reboot during Amazon’s annual planning process in November. The company is cutting hundreds of junior store manager jobs that executives deemed redundant and being more selective about where it puts stores. Rather than trying to scale up in multiple regions, Amazon is concentrating for now on a few key areas, including Illinois, Southern California, Northern Virginia and Washington state. It’s planning marketing events to reintroduce shoppers to the first renovated stores, in Schaumburg and Oak Lawn, near Chicago. Three more in Southern California are being renovated now, and the remaining 39 could be refitted if shoppers like the new concept.

Inside the stores, the emphasis is on traditional retail touches, not the technological flourishes Amazon introduced with fanfare when it opened the chain. “All the look and feel and design is very different to our existing Fresh stores,” Hoggett says. “Customers respond to a bit more of a bright and airy and light experience.”

Shoppers can still skip the line by using Amazon’s Dash carts, which identify items placed inside and display a running tally. The latest iteration of the carts rolled out last year and replaced computer vision algorithms with more basic bar code scanners embedded inside, backed up by a scale. In another sign that Amazon is looking to simpler solutions, the redesigned Fresh stores feature self-checkout lanes, though shoppers at many Fresh stores can still use the Just Walk Out cashierless technology pioneered in the company’s Go convenience stores.

“The customers that enjoy Just Walk Out in the Fresh stores, they really love it,” Hoggett says. “But we also recognize that it’s so new for many, many customers. The whole point for us is everybody’s welcome in our stores.”

For the most part, Whole Foods has been largely siloed from Amazon’s other grocery businesses. Hoggett, who moved with his family to Austin and works out of the grocer’s downtown headquarters, is starting to change that. Whole Foods executives now oversee all of Amazon’s grocery real estate and branding, while a longtime Amazon executive leads Whole Foods’ technology teams. Hoggett has brought in colleagues from his Tesco days with deep industry experience, including Claire Peters, who leads worldwide strategy for Amazon Fresh online and in-store, and Peter Bowrey, who leads store operations.

Amazon has hired retail veterans previously, but their influence wasn’t readily apparent in the Fresh stores, says David Bishop, a partner with Brick Meets Click, a grocery and retail consultant. “There were bells and whistles when they opened that look better in theory than reality,” he says. “The new group says, ‘People like coffee and doughnuts, we need coffee and doughnuts.’ This is the new guard. These people aren’t technology people.”

Bishop says Fresh seems to be trying to find its own industry niche: cheaper than mainline full-service grocers owned by Kroger or Albertsons Cos., if not as cheap as Walmart or Aldi, the German giant that is the fastest-growing grocery chain in the US. In addition to delivery fees, Amazon Fresh tries to defray the costs of e-commerce with prices that, in a recent check Bishop conducted, stand about 13% higher online than in-store.

Hoggett is betting Amazon can emerge as a one-stop shop for groceries. Surveys show households tend to shop at multiple markets depending on whether they’re stocking up on staples or preparing a special meal. “We think we can bring that four or five different grocers down to one or two, with Amazon being one of those grocery relationships,” Hoggett says.

To get there, he’s taking a step grocery watchers have been predicting since Amazon bought Whole Foods: letting people get their Coke and Doritos at the organic grocer. Those items won’t appear on store shelves, which still adhere to the chain’s pre-Amazon quality and ingredient standards. Instead the company will see if shoppers are keen on ordering their guilty pleasures online and picking them up at their local Whole Foods.

That—and creating a single online shopping cart for Whole Foods, Fresh and Amazon.com—will require new infrastructure. Among the planned changes: adding refrigerated sections to Amazon’s urban warehouses and putting more Whole Foods products in Amazon Fresh distribution hubs. In the New York area the company is testing a new, fully automated facility in Bethpage, on Long Island. The warehouse, which will open later this year or early next year, relies on technology from AutoStore Holdings Ltd.

If Amazon wants to become a leading player in groceries, it will require hundreds more stores, according to analysts. Whole Foods is working on an additional 50 locations, Amazon says, and hopes to build its roster of stores in development to 100 in the next few years. Fresh, which currently operates 44 stores, will likely resume its expansion if shoppers and executives are satisfied with in-store tweaks. Amazon could also bulk up by bidding on stores that Kroger and Albertsons are expected to offload as part of their pending merger.

“We’re very deliberate about growing a big physical store grocery network in the US and around the world,” Hoggett says. “We’re still working out how best to do that. I wouldn’t comment on anything we might do, but we will open more grocery stores.”